Interview with Troy Paiva

|

| Cockpit Shell - Green by Troy Paiva |

So, what’s the whole back story behind Lost America?

The progression goes like this: I've been attracted to, and explored, abandoned places since I was a child. It started out on road-trip-based family vacations where we would just drive across the desert for days on end. We visited Bodie in 1973. This was before it was a well-known tourist spot. When we arrived you could just drive into the center of town and park. No one else was there, we had the whole place to ourselves and I wandered around in that town alone all afternoon. My impressionable thirteen year-old mind was blown that a whole city would just be discarded like that. I was totally hooked.

All us Paiva's love the open road. My brother Tom and I have both had long-distance driving jobs and our father was a pilot. We're descended from countless generations of fishermen, so helming vehicles across vast expanses, under huge skies is just built into our DNA. As a teenager my friends and I would take three-day, 1,500 mile drives into the southwest. I learned at a very early age that the journey was frequently more interesting than the destination. This driving obsession led me to lots of little traveled places in the middle of nowhere. Remember, this was the late '70s, when the last remote stretches of interstate were being opened, so there was lots of freshly abandoned stuff to see out there. By the time I had reached my late teens I was a full-blown road-tripping ghost-towner and ruins nerd.

One of Tom’s classes was Steve Harper’s semester-long night photography program. When I saw some of the work being done by Steve, Tom and some of the students like Tim Baskerville (eventual founder of “The Nocturnes”) and Lance Keimig (eventual author of Night Photography: Finding Your Way in the Dark) I immediately saw night work’s potential for capturing the haunting souls of the ghost towns and junkyards of the West that I’d been drawn to since I was a child.

Steve let me audit a classroom lecture by Michael Kenna and tag along on some class shoots in the industrial section of San Francisco. I immediately jumped on the bandwagon, bought a junky old 35mm Canon FX, my first real camera, and started my photography career making 8-minute exposures of abandoned Route 66 buildings, under the full moon.

It didn’t take long for me to come around to the idea of adding light during the time exposures. I began experimenting with strobe and flashlights to add details to the shadow areas. For a long time I really did just sorta wing it, throwing light out there without a lot of thought.

Right before the turn of the century, I began to work with some early 3D modeling and rendering software. It was quickly apparent that effective lighting was the key to good 3D work and I concentrated on studying the nuances of artificial lighting and its effect on mood and emotion. It had an instant impact on my photographic lighting–it began to have intent and context.

| "Trad'r Rix Tiki Island" by Troy Paiva |

O. Winston Link blew both our minds. Even as a non-photographer, his subjects: trains, cars and a sped up modern world fueled by postwar technology, all hit me right in the sweet-spot. Here was another layer of Lost America–a lost world of highballing locomotives, gravity feed gas pumps and drive-in theaters. More proof of concept for me. But then you dig into his process and that’s where his work really gets miraculous.

|

| Photo by O. Winston Link |

|

| Photo by Chip Simons |

|

| Photo by William Lesch |

I was a good fit to work on Micro Machines because it was an area I was really knowledgeable about already. Along with literally hundreds of cars, I also designed a whole pile of playsets of car washes, gas stations and restaurants too. In many ways it fulfilled my childhood desire to be an architect, without requiring all that pesky engineering and math knowledge.

|

| Click to see larger |

|

| Eon 66 by Troy Paiva |

Even though most of the things that made night shooting technically difficult have been simplified by the invention of the DSLR and digital darkroom, you still have to go out and brave the elements. You still have to spend hours out there, just to get a couple of finished images. You still have to deal with cops and property owners. You still have to make the effort to find something interesting to shoot.

In today's sped-up O.C.D. culture, there are very few people with the patience to sit back and relax, spending 30 or 45 minutes doing a series of 4-minute exposures to get one shot. Everyone today wants to do everything with one click of the camera, one click of the mouse. This is why almost no one paints, or plays a musical instrument anymore. No one wants to put in the time to become really good at something. It's tragic, really.

|

| Upstairs by Troy Paiva |

The fact that all my early work looks so grainy, vignetted and color shifted, presaged today's iPhone "Hipstamatic" and toy camera craze, has amused me to no end. Nowadays I see people putting Holga lenses on $2000 digital bodies, so it's come full circle and people have embraced and understood the aesthetic. But yeah, back in the '90s and early '00s, I took a lot of flack from the rest of the night shooting community about my crappy gear.

|

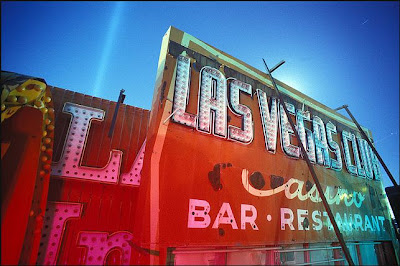

| Las Vegas Club by Troy Paiva |

|

| MS by Troy Paiva |

I will establish a base camp in a cheap motel, usually in a small town, out in the middle of nowhere. I used to work out of a pick up with a camper shell. I'd sleep for a few hours in it, a few miles down a dirt road, or behind an abandoned mine–someplace far from paved roads. Over the years, I've found I do better work, and more of it, when I can get some sleep and a shower in an air-conditioned room. Yeah, I've stayed in some terrible dives, but it beats sleeping in an oven with no running water.

During the afternoon I'll drive out and start scouting locations. I'll stop when I find something interesting, walk around, take a few pictures, see if anyone notices me. I'll think about it in the context of night. Will the location be bathed in ugly sodium vapor streetlight? Will car headlights be a problem? Neighbors? If it's a business like a junkyard, I'll try to talk to the owner, show him some work and see if I can get in later that night. I'll continue on, compiling a list of possible locations, in a 50 or 100 mile stretch, until dark. Then I'll turn around and shoot my way back to the motel by 3 or 4 AM. Sleep 'til noon, grab a diner breakfast and repeat!

I used LED flashlight down the passenger side from the back of the car, just out of the frame. Getting some light on the ground was important there too, giving the left edge of the frame some context instead of the car just floating in black space. Then I crouched behind the car and used the LED on the motel sign, making sure to hit the further away top section a little more than the closer lower section, so the whole sign would look evenly lit. Coming round to the front, I popped a red-gelled strobe where the engine used to be, through the grille. There is also a snooted LED on the “M” logo and headlight from camera right. Note that I also just touched the broken headlight with light too, only enough to catch a glimpse of the dead wires in the socket, but not so much that it looked lit.

|

| Traveler's Motel: 1957 Mercury by Troy Paiva |

This Chevy Monte Carlo was lit with lime- and green-gelled Stinger. The intensity of that light meant backing about 50 feet away from the car, softening and spreading its area of luminosity to cover the entire car without moving it. This gives a smooth, even look to the light it casts. Note that I lit from a low, shallow angle and included the foreground, again, to give the car a sense of place and weight I also used a tumbleweed as a gobo to cast a shadow on the rear fender. The red interior was done with an LED pointed at the camera from the far side of the car, blocked by the roof’s rear sail-panel. I rotated it around inside the car so the dirty glass would diffuse the light. In post, I used the clone tool to tidy up some slight lens flare and get rid of a distracting point of light on the horizon. There was a little dodging, to pull some details out of the moonlit background areas, too.

|

| Monte Carlo Moonrise by Troy Paiva |

There’s already a ton of night photography workshops out there, what made you and Joe Reifer decide to offer another one?

See, it's easy to teach a night photography workshop because there's actually something to teach; equipment that people aren't familiar with, unusual exposure formulas and other hard factual data.

But it's difficult to find a night photography workshop that goes beyond the technical and dives into why you take photographs. Most of these other workshops just teach you how to take night photographs. Our workshop teaches you how to take good night photographs.

At Paul's there's no down time driving from location to location. You can become immersed deep in the work and can be highly productive in a place that's totally off the map where only a handful of people have ever taken pictures. We had one student come home from one of our three-nighters with 47 amazing time exposures (David Evan's photos from the Paul's Junkyard workshops). Granted, he's an experienced night shooter working with multiple cameras, but try making a body of work that big and cool at any other night photography workshop!